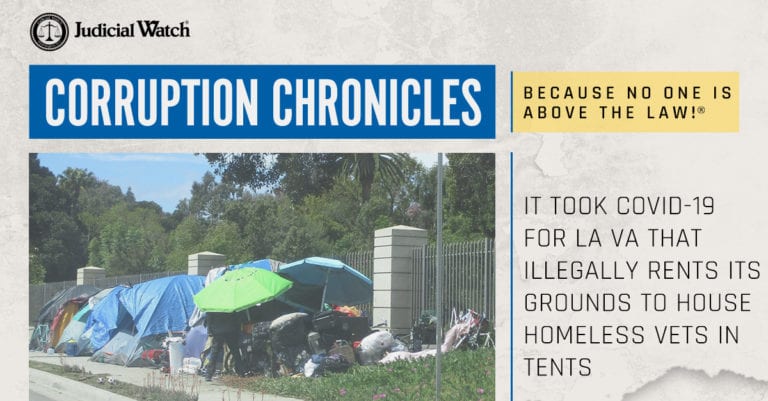

It Took COVID-19 for LA VA That Illegally Rents Its Grounds to House Homeless Vets in Tents

It took a global pandemic for the Los Angeles Veterans Affairs to offer a few vets temporary housing on a sprawling parcel deeded to the federal government over a century ago for the specific purpose of caring for disabled military veterans. Thousands of veterans have long lived on the streets surrounding the lush facility in West L.A., yet the VA has been derelict in its duty to help them. With the COVID-19 crisis deeply impacting the region’s vast homeless population, the VA finally erected several small tents in the parking lot of its healthcare system campus to accommodate a couple dozen vets who were sleeping on the sidewalk immediately adjacent to the grounds. It is a tiny gesture that will barely put a dent on the crisis, but it’s a start, say some local veterans.

“Honestly, it’s like a Band-Aid considering that there are around 4,000 homeless veterans in the city of L.A.,” said Robert Rosebrock, a U.S. Army veteran and activist who leads a troop called the Old Veterans Guard. Since 2008 the group has assembled at the “Great Lawn Gate” that marks the entrance to the Los Angeles National Veterans Park to protest the VA’s failure to make full use of the property to benefit veterans, particularly those who are homeless. The elderly vets have been a thorn in the agency’s side and federal authorities have retaliated against them for denouncing the fraudulent use of the facility, including a scam involving a VA official who took bribes from a vender that defrauded the agency out of millions. VA police harass and intimidate the senior vets at their weekly rallies and Rosebrock got criminally charged for posting a pair of four-by-six-inch American Flags on the outside fence on Memorial Day in 2016. Judicial Watch represented Rosebrock in the federal case and a judge eventually ruled that Rosebrock was not guilty of violating federal law for displaying the flags above the VA fence. In the meantime, the VA illegally rents its grounds to institutions that don’t serve veterans and evicts groups dedicated to helping them.

That fuels Rosebrock’s passion to help needy vets. Tireless at 78, he has made it his mission to fight for those who served their country but continue to be neglected by the VA. It enrages him and his group that the 338-acre West L.A. property, dedicated to the federal government in 1888 to serve disabled vets, is used for many unrelated causes. Among them is a stadium for the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) baseball team, an athletic complex for a nearby private high school, laundry facilities for a local hotel, storage and maintenance of production sets for 20th Century Fox Television, the Brentwood Theatre, soccer practice and match fields for a private girls’ soccer club, a dog park and a farmer’s market. “There shouldn’t be one homeless vet in L.A.,” Rosebrock said. “That’s what this facility is for; to help them.” He reminds that back in 2014 L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti publicly guaranteed then First Lady Michelle Obama that he would end veteran homelessness in his city by the end of 2015. Judicial Watch reached out the to the mayor’s office but never heard back. “There are still thousands of vets sleeping on the sidewalk right outside the fence,” Rosebrock said, offering heart-breaking pictures.

One somber photo has plastic tarps, tents, umbrellas and an assortment of ragged items covering the swale adjacent to the VA fence on Veterans Parkway. It includes a large pile of the homeless veterans’ belongings stashed in white plastic trash bags, suitcases, lawn chairs, wheelchairs and bicycles. Surrounding areas around the VA fence perimeter are also captured in grim shots—snapped recently by Rosebrock—that depict impoverished shanty towns in the middle of some of the city’s most upscale communities. Battered tents, decaying tarps, buckets, grocery store carts and black plastic trash bags full of personal belongings line sidewalks and, in some areas, laundry hangs on the VA fence. Not far away are ritzy neighborhoods like Brentwood, Westwood and Century City.

In a recent local newspaper article the VA claims that the new parking lot tents are a “service center” instead of a campground. Bathrooms, showers, security as well as medical and psychiatric care are also provided to the lucky few. The story says the temporary shelter has a reduced capacity of 50 people to accommodate social distancing that reportedly helps prevent coronavirus from spreading, but Rosebrock, who visits the site regularly, said the real number is more like 25. The tents are too small, he says, and older vets have difficulty crawling around in them. Rosebrock bought a larger tent and tried donating it, but the VA rejected the offer. Judicial Watch has also offered to purchase tents for the homeless veterans. “There’s no rhyme or reason for offering such a limited number of veterans tents,” Rosebrock said. “It’s just an arbitrary number they came up with.”